The current state of progressive web apps

Web apps have long played second-fiddle to native ones. While mobile apps benefit from full access to device APIs, snappy performance and support for features such as offline content and push notifications, the stateless and browser sandboxed nature of the web has frequently relegated web-based apps to second choice.

However, in recent years we’ve seen the tide start to turn, particularly with the growth in popularity of client-side rendering and the increased OS-level support for native only features such as background fetching. This new breed of websites are frequently termed progressive web apps (PWA), but what does that actually mean?

Defining progressive web apps

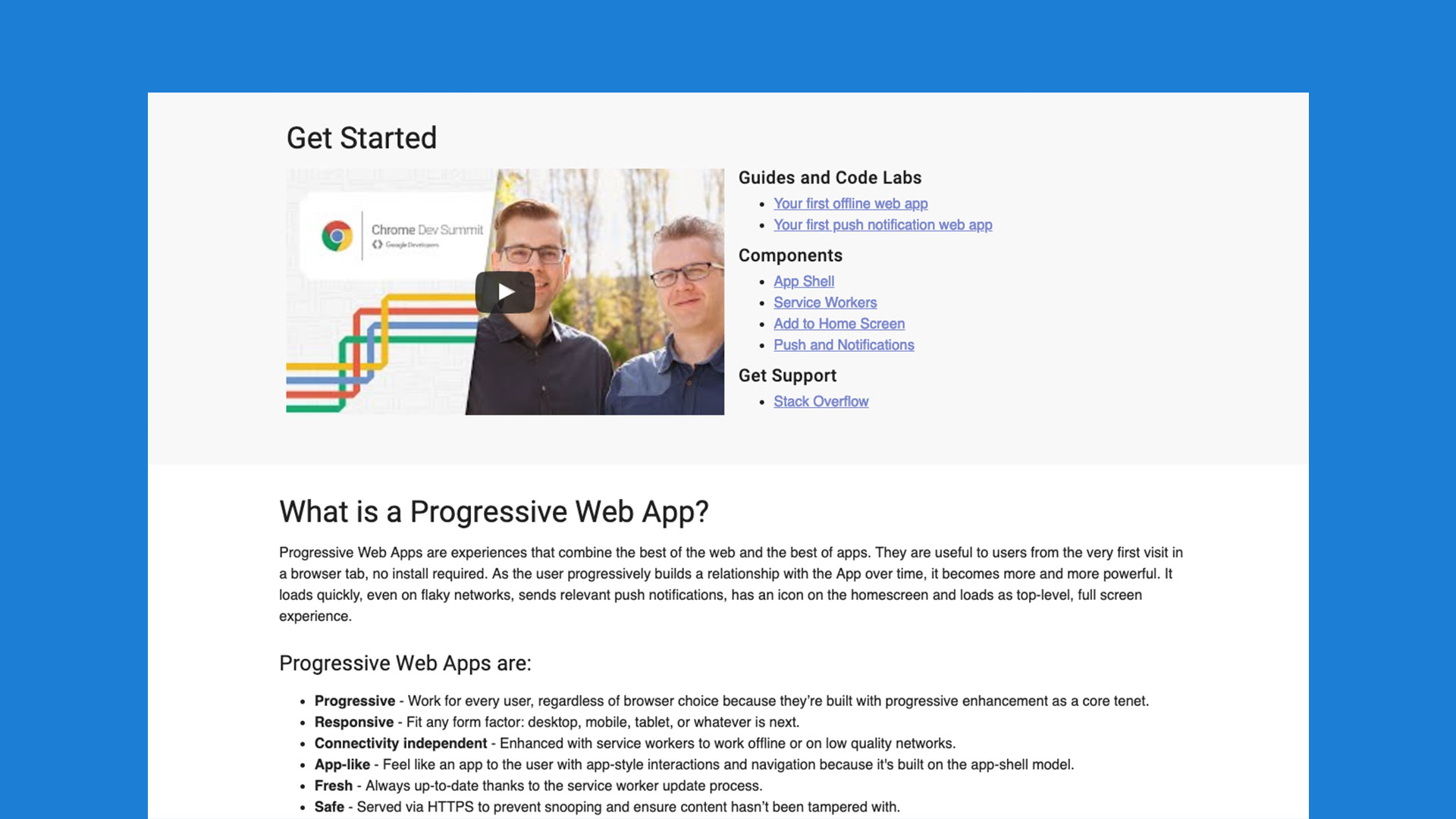

Originally coined by husband-and-wife duo Frances Berriman and Alex Russell (and now championed by Google), PWAs were initially defined as:

- Progressive – work for every user, regardless of browser choice because they’re built with progressive enhancement as a core tenet.

- Responsive – fit any form factor: desktop, mobile, tablet, or whatever is next.

- Connectivity independent – enhanced with service workers to work offline or on low-quality networks.

- App-like – feel like an app to the user with app-style interactions and navigation because it’s built on the app-shell model.

- Fresh – always up-to-date thanks to the service worker update process.

- Safe – served via HTTPS to prevent snooping and ensure content hasn’t been tampered with.

- Discoverable – are identifiable as “applications” thanks to W3C manifests and service worker registration scope allowing search engines to find them.

- Re-engageable – make re-engagement easy through features like push notifications.

- Installable – allow users to “keep” apps they find most useful on their home screen without the hassle of an app store.

- Linkable – easily share via a URL and do not require complex installation.

However, the current baseline technical requirements in order to make your app ‘installable’ (and therefore a PWA) are merely:

- Served over HTTPS.

- Includes a populated JSON manifest with some metadata about the site.

- Includes a service worker (a background script that sits between the client and the server which is capable of intercepting requests)

It’s this final stipulation, the service worker, which enables the app-like push-notifications, offline support and background updates. However, crucially, all that’s required to meet the PWA technical requirements is that the service worker is present – it doesn’t actually need to be functional or implement any of these features.

Add to this that most modern sites are already served securely, and I’m sure you can see that it’s easy to meet the progressive web app requirements with a minimum of effort. Note, though, that this doesn’t necessarily mean that a given site fulfils the ‘app-like’ qualities that the PWA name (and original definition) suggests.

Defining app-like

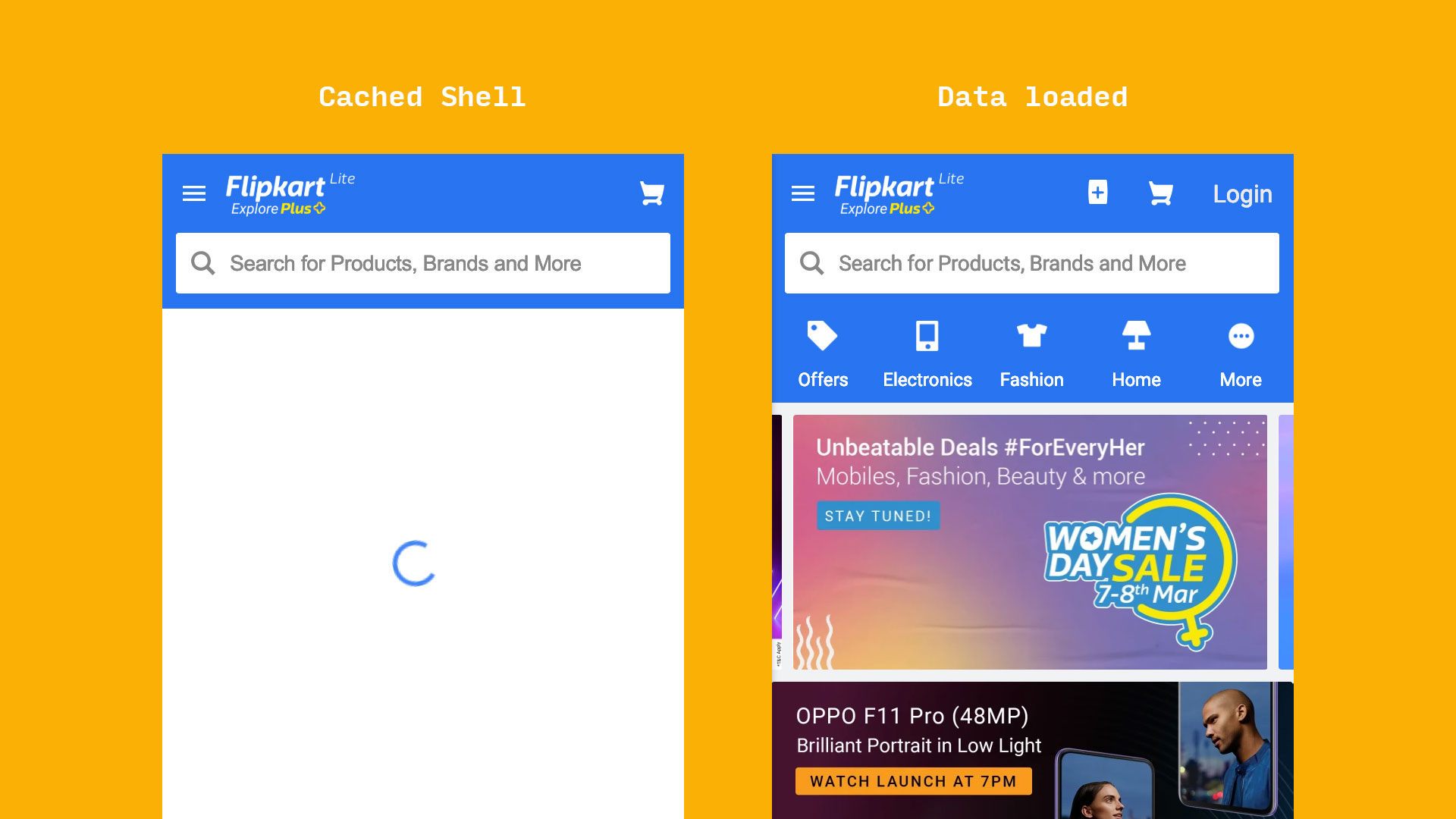

When people think of an ‘app-like’ website, they are usually referring to a SPA (single page application). Instead of dynamically building the site on the server for every request, the same (empty) page is served for all visitors alongside a bundle that contains the application.

In many ways this bears more similarities to how native applications behave than traditional websites – the shell of the application is downloaded to (and runs directly on) the client, followed by content updates dynamically pulled in from an API. Since navigation and interactions happen on-device (instead of requiring a round trip to the server), user-interactions feel ‘snappy’ and instant. This is what Berriman and Russell are referring to with the ‘app-shell‘ model.

However if your application or website wasn’t built this way from the outset, adopting it would necessitate a complete re-think of the product’s architecture, which is usually not viable. Traditional server-rendered sites still dominate the web and likely will for a long time to come, which is probably why (as Jason Grisby notes) Google’s definition of a PWA has since become the more nebulous trifecta of ‘reliable’, ‘fast’ and ‘engaging’. Even with a traditional website, it’s possible to score well in the progressive web app category on tools such as Google’s own Lighthouse.

While all sites can (and probably should) implement the baseline PWA requirements – no site wouldn’t benefit from basic offline support, discoverability and HTTPS – the term by definition no longer differentiates between client and server rendered sites. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that it means different things to different groups, and that the expectations around it (and marketing or sales thereof) has become somewhat muddied.

Bad PWA behaviour

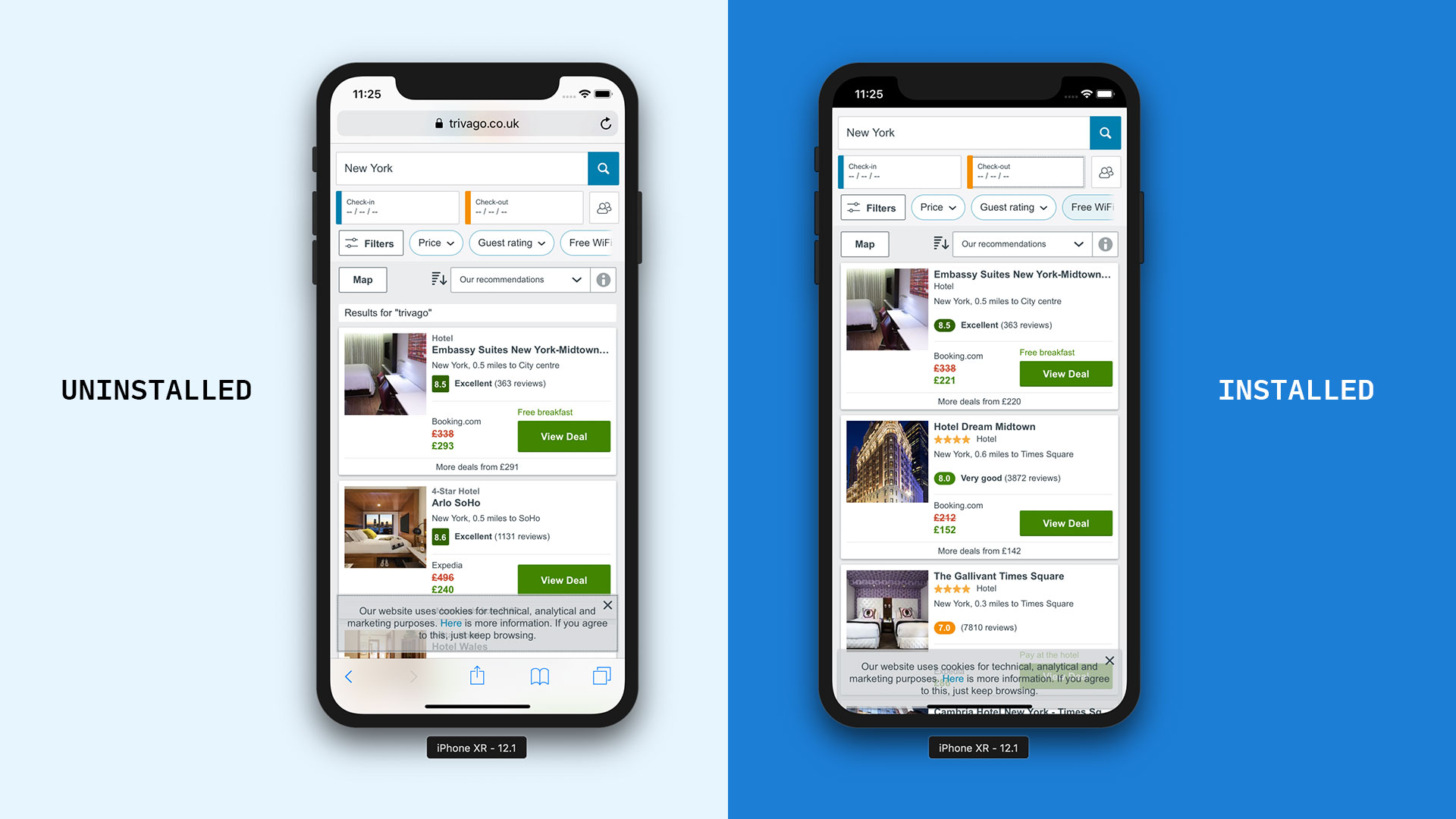

Unfortunately, the desire to create a more native-style experience can lead to creating a worse PWA experience than the in-browser mobile site provides.

For starters, the app-manifest allows (although does not require) developers to hide the browser ‘chrome’, containing the share-sheet and address bar. By doing so we immediately remove two core tenants of the original PWA vision: share-ability and link-ability. Gone also is the ‘refresh’ button, meaning there is no way of reloading the page in the event of an error (short of restarting the application).

Even worse, on iOS, the application state is currently not persisted. This means that every time the PWA loses focus (e.g. you switch to a different app), it restarts. It’s possible to manually save the application state/current page and restore it on load, but this would have to be written as custom functionality, and the start-up time would be incurred every time focus is switched.

Although it’s still early days on iOS (support for service-workers was only recently introduced in version 11.3), it’s hard, at the time of writing, to recommend ‘installing’ a site as a PWA on the platform for this reason.

Looking forward, past the PWA

There’s a lot to be admired in the core tenants that Berriman and Russell defined, however, we have to be careful in our adoption of the progressive web app term, given its now rather flimsy definition. Berriman herself says:

‘The name is for your boss, for your investor… it’s marketing, just like HTML5 had very little to do with actual HTML. PWAs are just a bunch of technologies with a zingy-new brandname that keeps the open web going a bit longer, that helps it compete with the proprietary, the closed, until the next thing (and hopefully the next thing) comes along to keep it sharp and relevant.’

Of course, as support for progressive web app-based sites improves on iOS, we’ll continue to benefit from the PWA’s only truly functional requirement: the service worker. Background updates, push notifications and full offline support are all fantastic additions and will go a long way to negating the need for a traditional cross-platform ‘native’ app.

In the meantime we should, as ever, base our decisions about what technology to use in a given situation on what’s best for the user or client, rather than on what’s garnering the most blog posts.