The issues with JAMStack: You might need a backend

Great applications deserve great marketing sites, which is why we’re always on the lookout for new developments and trends in content management systems (CMSs). While traditionally a space occupied by open-source giants such as WordPress and Drupal, ever since the Smashing Magazine relaunch back in 2017 there has been a resurgence of interest in static-sites.

Given the (sometimes self-inflicted) complexity of modern front-end development, the desire to return to the simplicity of plain HTML is perhaps unsurprising — after all, many of today’s problems (performance, async data, caching etc) are either irrelevant or come as standard with the removal of a dynamic server-side language.

While there are many vocal proponents of modern static sites, the biggest champion is Mathias Biilmann of Netlify, who is responsible for the somewhat absurd sounding ‘JAMStack‘, and has helped popularise static-based workflows with tools such as a static CMS and e-commerce API.

The JAMStack has become so popular it even has its own newsletter, birthing a whole ecosystem of plugins, services, articles and even conferences. So what exactly makes it different?

Defining the JAMStack

The JAMStack boils down to:

- JavaScript to handle async data requests/interactivity.

- APIs to handle dynamic data retrieval/requests.

- Markup compiled into static HTML files.

Despite the original acronym, these principles could easily apply to Jekyll blogs of yesteryear. The difference is characterised by the advanced tooling, workflows and ecosystem that have sprung up to accommodate the renewed interest. By combining the modern tooling of Gatsby with services such as Formspree and a ‘static’ CMS (such as Netlify’s own), the JAMStack suggests that static-sites need not be relegated to esoteric developer blogs or hobbyist sites, but are serious contenders for client projects.

The purported benefits include performance gains, improved security and an escape from the bloated content-management systems we have become accustomed to:

“It’s a new way of building websites and apps that delivers better performance, higher security, lower cost of scaling, and a better developer experience.”

However, we think there’s more than a few reasons why you should give this particular innovation a miss:

Enforced minimalism

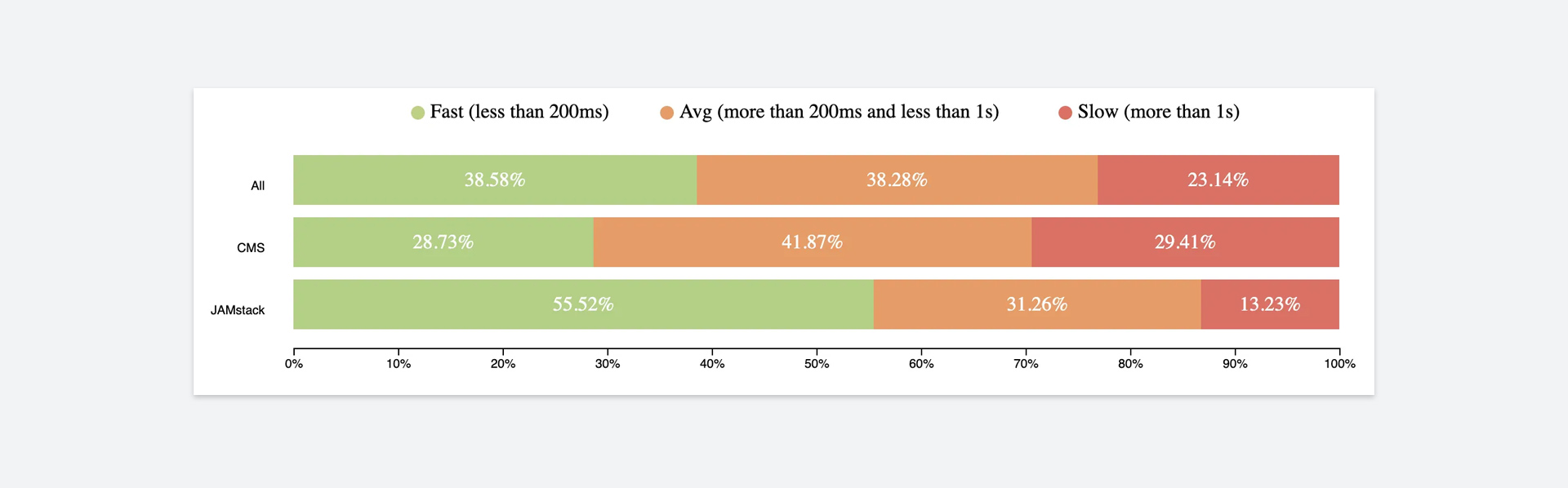

Unfortunately, nearly all of the advantages of a static site are simply due to enforced minimalism. For instance, TTFB performance will be the best it possibly can be (all else being equal), since there is no overhead to serving pages that come with dynamically generated content. The site will be considerably more secure only by virtue of there being no server-side language or database to provide a vector for intrusion. Hosting will be more economical and scaling will be infinitely easier because there are no requirements for a server-side language or database.

To say a static site is faster, more secure and more scalable is undeniably true, but it’s akin to removing the engine from a car and heralding it as a more economical means of transport. If the features were expendable in the first place, then the real question is why they were included at all.

It’s true that it’s easier to start lean than it is to make something slow and bloated quicker, but a well-configured full-page cache (using something like Redis or FastCGI) will effectively give you the performance of a static-site for ‘free’. Even Eric Meyer’s recent plea for sites to ‘Get Static‘ so they may better serve the traffic demands of a COVID-19 world suggests this:

“I can’t tell you how best to get static—only you can figure that out. Maybe for you, getting static means using very aggressive server caching and a cache-buster approach to updating info.”

Immature (but complex) tooling

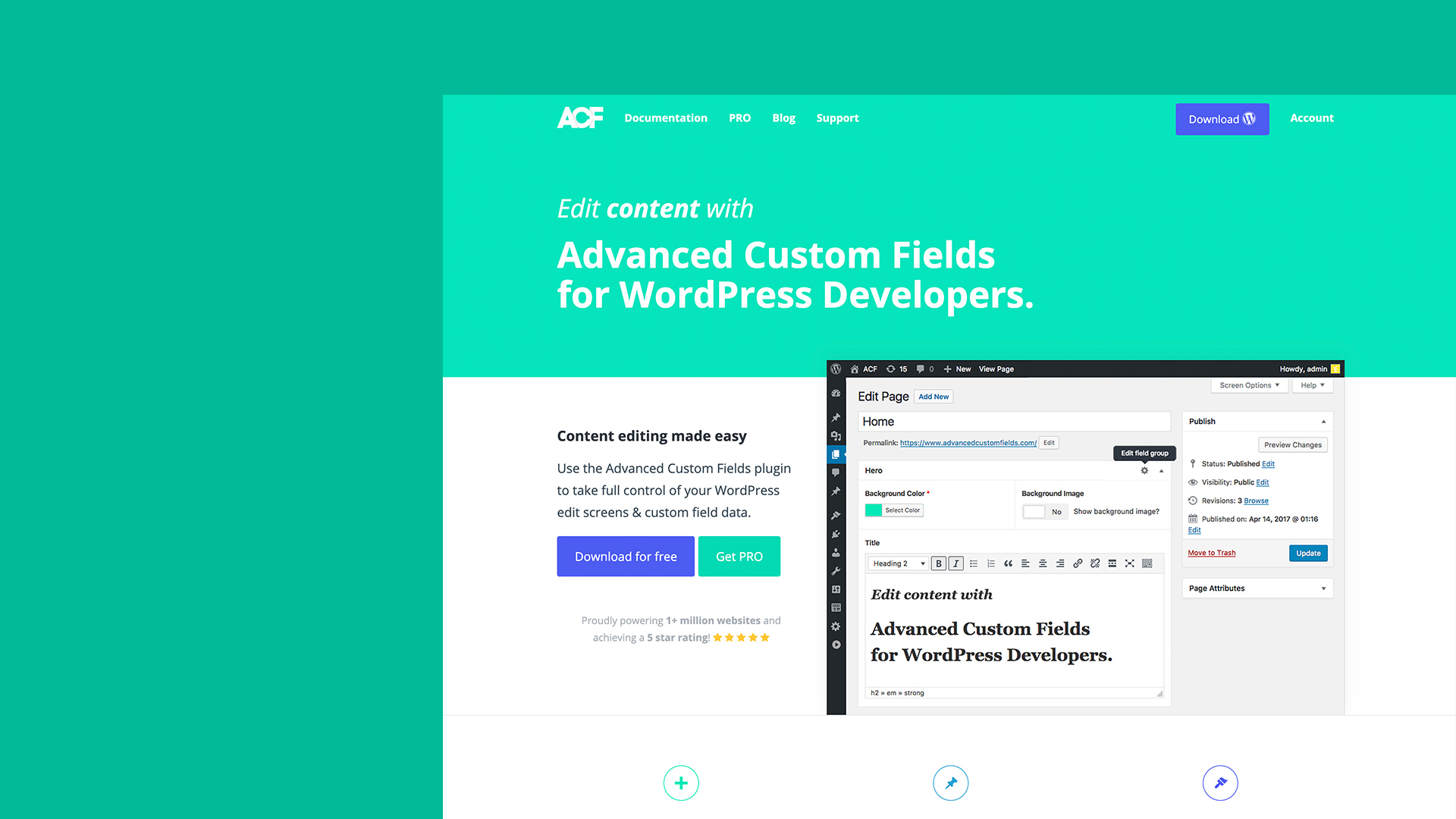

While tooling has come a long way, most static-site builders don’t provide anywhere near the flexibility of more traditional CMSs or server-side frameworks. Basic features such as named/aliased routes are rarely present, and the Netlify CMS (while interesting) will struggle to rival the editing experience of Craft’s Matrix or ACF’s Flexible Content Fields. Anyone who has spent more than a couple of hours with modern CMS-as-a-service offerings knows how much they’re lacking compared to their predecessors, missing key features all the way from conditional inputs through to required fields.

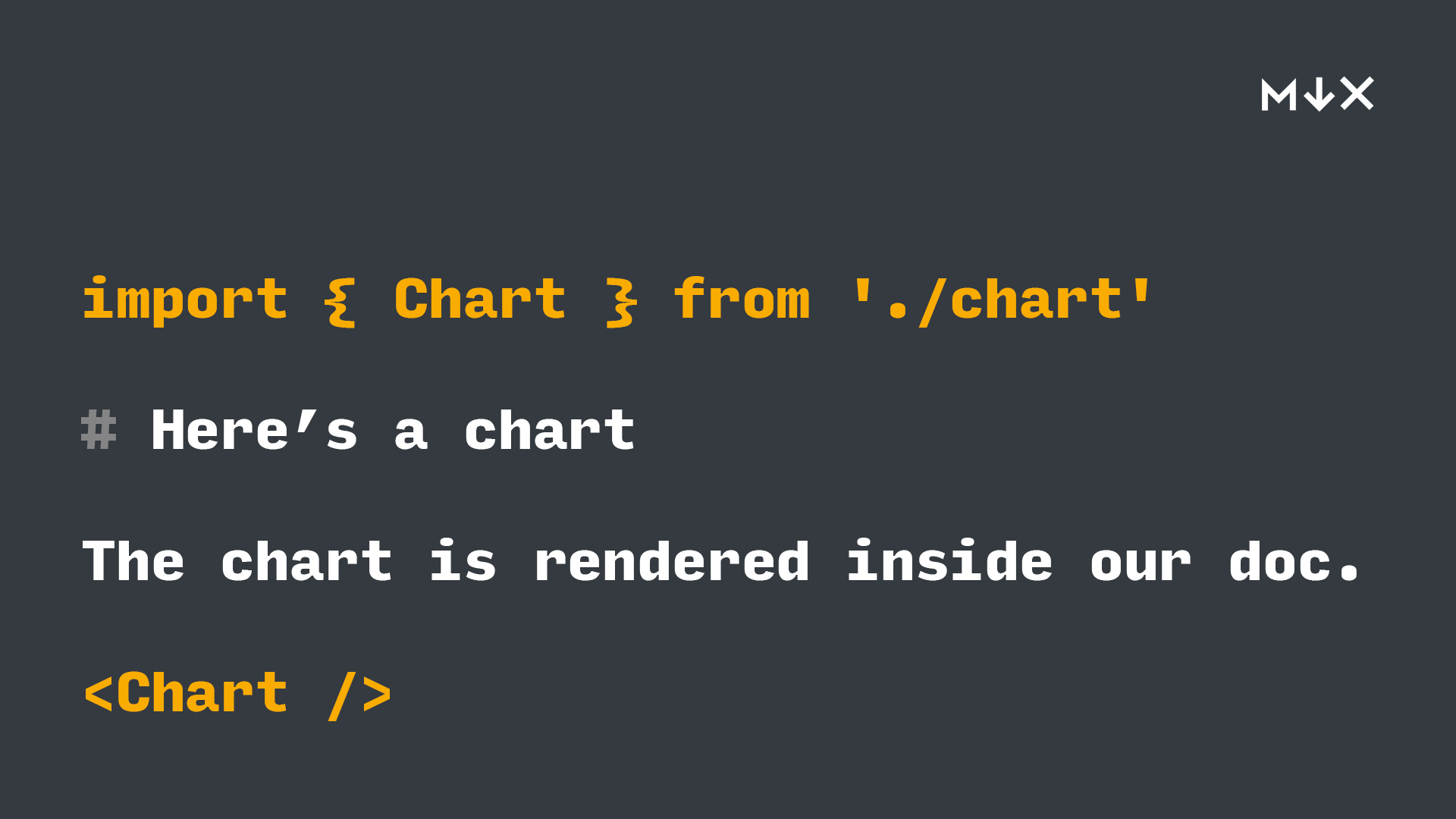

Ironically it’s the content-editing experience itself which suffers the most from the JAMStack approach since, despite the developer obsession with plain text, it’s surprisingly painful to create complex editorial content without the aid of a configurable CMS. If you imagine a content-builder with variable content types and related-entity fields, this becomes extremely problematic to represent in Markdown, unwieldy as YAML and counterintuitive as JSON – especially with long-form content.

Moreover, if you decide to avoid the CMS and just enter these as front-matter yourself (which admittedly works), you’ll be entirely responsible for remembering the fields and their types yourself. Forget the type-checking, restrictions (such as related entity/foreign key constraints) and the conditionals afforded by conventional CMSs.

As a result, it’s hard to provide anywhere near as robust an editing system as any CMS on the market. This isn’t just an issue for ‘less-techy’ editors, but a serious inconvenience for all involved.

Fighting the JAMStack system

The most perplexing JAMStack case-studies are not those which are static marketing sites, but those with a genuine need for dynamic features.

Smashing Magazine itself requires advanced search capabilities, basic e-commerce features, a multi-user CMS and an integrated comments system. These are integral features to the success and functionality of their business and have already been excluded by their choice of stack.

Instead of these being your problems (as the developer), and choosing if/when to farm them out to third-party services, the JAMStack leaves you with little choice other than to distribute responsibility to a variety of (often unproven) 3rd parties. In much the same way as server-less is just “someone else’s server”, the JAMStack usually requires “someone else’s backend”.

Reading the dependency list for Smashing Magazine reads like the service equivalent of node_modules, including Algolia, GoCommerce, GoTrue, GoTell and a variety of Netlify services to name a few. There is a huge amount of value in knowing what to outsource (and when), but it is amusing to note the complexity that has been introduced in an apparent attempt to ‘get back to basics’. This is to say nothing of the potential fragility in relying on so many disparate third-party services.

If you can be certain that a project will never require a ‘dynamic’ server-side feature, then perhaps the JAMStack is appropriate. However, the second you need a dynamic feature (such as a form or comments) you either have to rely on a 3rd party or build a separate API yourself (essentially creating a backend). This solves nothing, but instead just awkwardly spreads the responsibility.

This is even a minor blow for progressive enhancement since features traditionally provided for ‘free’ (such as form validation messages) and e-commerce options will require JavaScript, where before they did not. Anything dynamic must be client-side, meaning the more holes that need to be plugged the worse things become. This is not to mention the potential performance issues created by moving an abundance of logic (possibly unnecessarily) to the client.

Conclusion

There’s still a place for static sites on the web, but it’s shrinking, not growing, and likely still the domain of developer portfolios and side-projects. Sure, it’s possible to engineer a workflow in 2020 that manages to smoosh together a set of disparate 3rd parties, a version-control-system backed CMS and a bunch of template files into a working (and fast!) site, but the value is questionable. Instead of reducing complexity, the JAMStack just shifts it around.

Security and performance are real concerns and will undoubtedly continue to plague developers, library authors and product owners as long as software development lives, however, the solution won’t be found in a reduction of responsibility.

It’s fitting that we have taken the simplest form of a website — static HTML — and transformed it into a complex landscape of build processes, tooling and services that more than rivals the complexity it set out to supplant.