Apple’s move to ARM could reshape the development landscape

Back in 2015, AMD’s CFO, Devinder Kumar, made the prediction that by 2019 “15% of the overall server space is in the ARM server business.”

He was wide of the mark by some way; at the start of 2019, ARM-based systems made up precisely 0% of the server market. But could Kumar have been on to something?

Well, I think so.

But first, a note of caution. It’s been fashionable to predict the demise of the x86 server monopoly for a while now, but it’s still here and, seemingly, as strong as ever. So, what’s different this time; why am I writing this article now?

Well, in my view, a number of factors are converging to make change ever more likely. Namely, the huge scale of cloud computing providers, Apple’s plans to migrate their laptop products to ARM-based processors, and the opening up of the educational space to include ARM-based systems.

What is ARM?

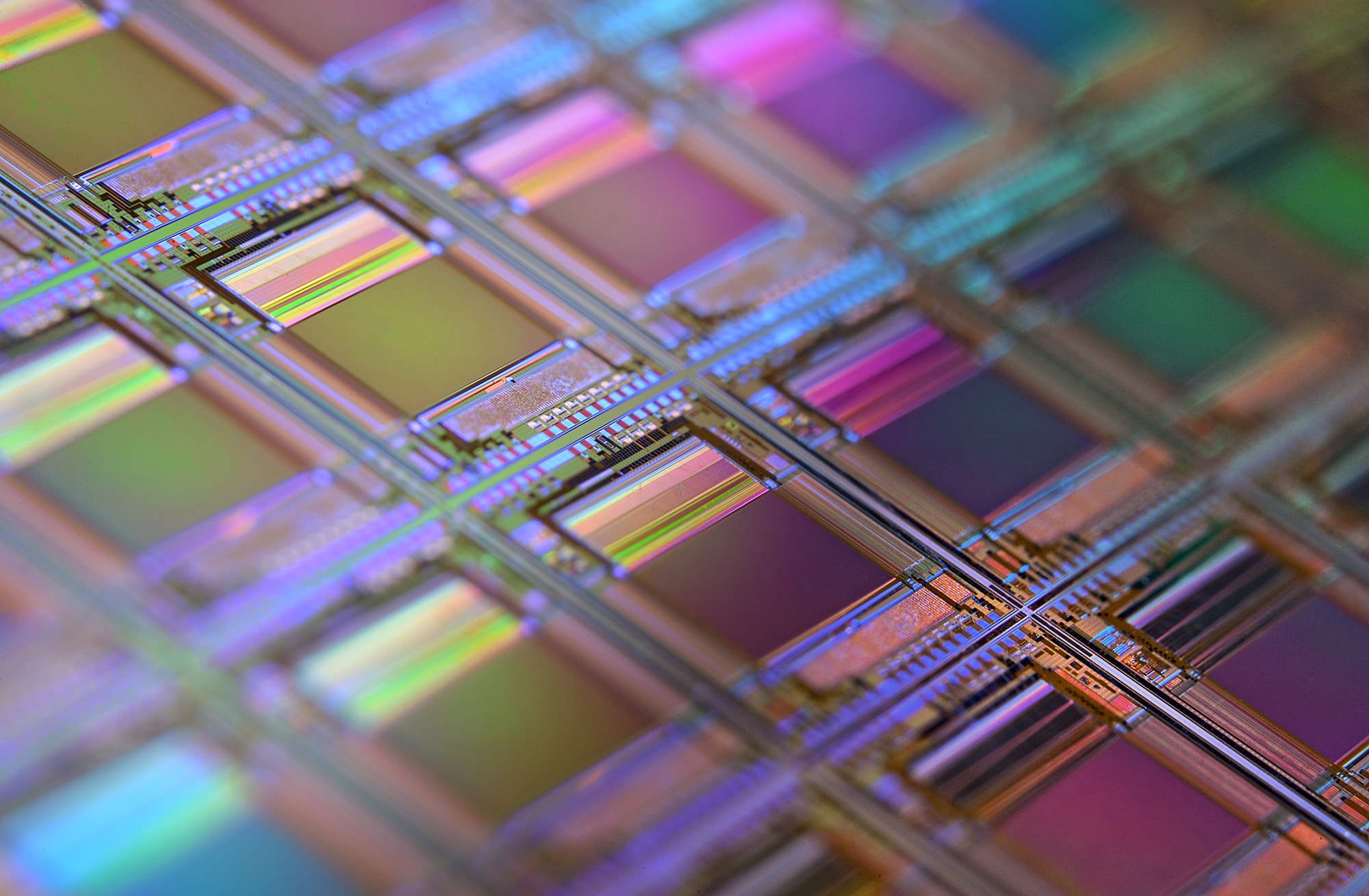

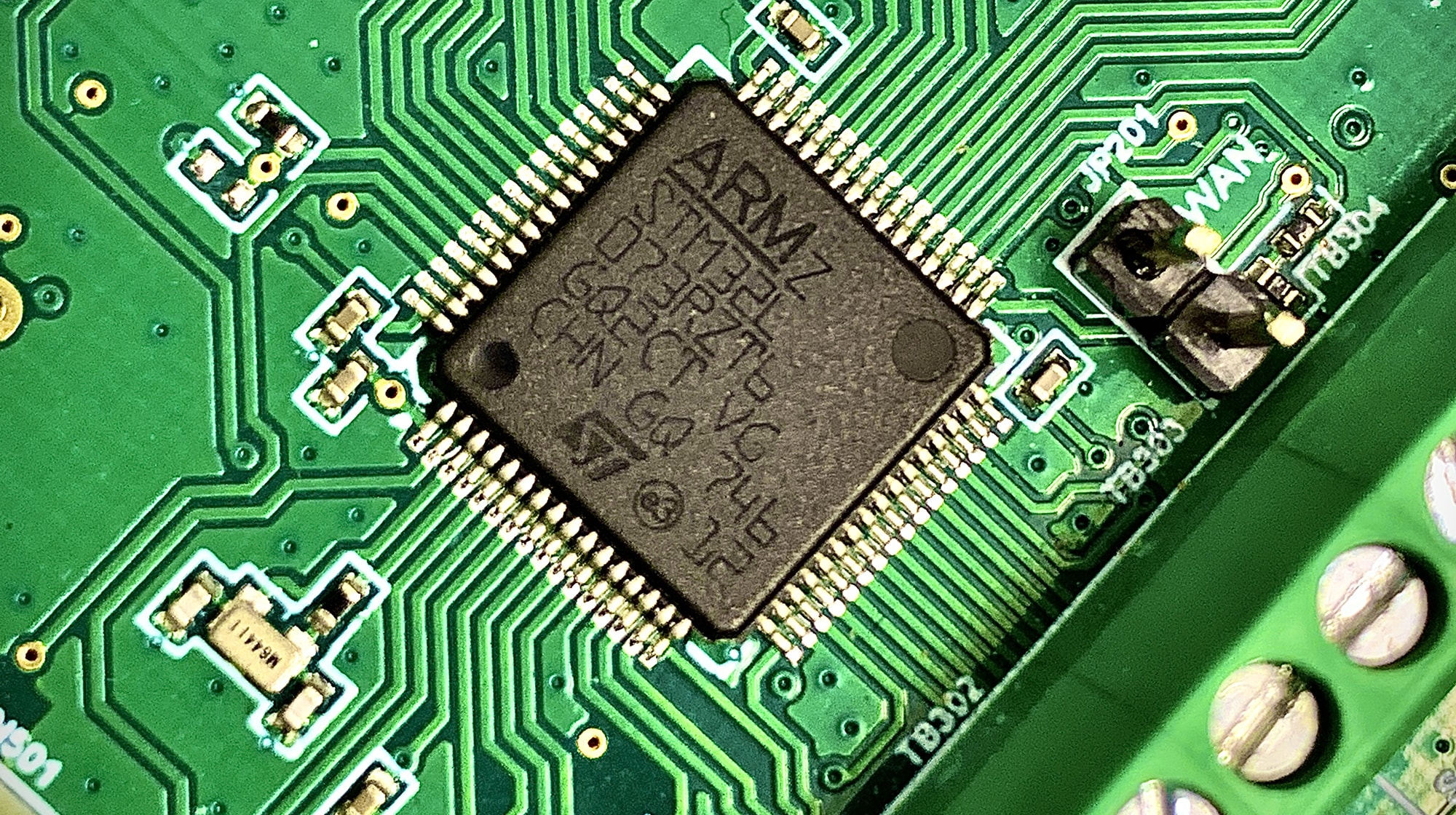

ARM is a computer chip architecture developed by Acorn Computers in the 1980s (ARM is an acronym of Acorn RISC Machine). The architecture of a chip denotes the language (known as an ‘instruction set’) that a given processor speaks.

ARM processors are wildly popular, powering everything from phones to industrial equipment. This is due, in part, to the unique way these chips are created – ARM designs the architecture, language and even specific modules or cores, and leaves it to customers to pick how they wish to put these together.

This means companies can tailor ARM chips to specific use cases, whilst still retaining broad support from existing programming languages.

One area that ARM chips haven’t made inroads into, however, is the server processor market. This is monopolised by processors designed and manufactured by Intel and AMD which use a different architecture called x86. Programs written for x86 processors won’t run on ARM processors, and vice versa, meaning if ARM processors were to penetrate the server market, customers would likely need to choose whether to rent time on ARM or x86 based servers.

Why is this worth talking about?

What instruction set the chip inside a server is based on may seem like a remote, trivial piece of information. For most people, it is, but at Browser we live and breathe web and server-based tools and products.

For us, more choice in the services available to us will always be a good thing. It’s good for our clients too. More choice means more flexibility in the systems we design and build, and more choice can often bring more competition and lower prices.

CPU architecture can have other, far-reaching impacts. ARM processors, for example, tend to perform well in terms of power and thermal efficiency, thanks to the way their instruction set works. In principle, this makes them look attractive to big data centre operators whose biggest cost is the electricity used to power and cool their servers.

Superior performance in this area produces a twofold benefit, reducing both to the cost of service, but also an organisation’s environmental impact. It’s common these days for cloud operators to prioritise performance per watt of power used over the peak maximum performance of a chip.

ARM as a server

Several attempts have been made to produce ARM-based processors that target servers, but they’ve never really been particularly commercially successful.

The primary reason behind this is the huge inertia that the x86 ecosystem possesses. After all, the x86 architecture offered by Intel and AMD’s chips has formed the backbone of personal and business computing for the last 40 years. There is no business case for rewriting all the software that has built up in that period to run on ARM processors.

However, as I mentioned previously, I think we’re at a point in history where there is a business case for bringing ARM processors into the server market in a more targeted way.

Scale brings options

The rise and rise of the big cloud providers, such as Amazon and Google, grants these companies such scale and resources that it’s worthwhile for them to examine designing and building their server infrastructure in-house.

This started at first by customising and producing the hardware elements around the processors. Examples of this can be seen in Amazon Web Services’ current ‘Nitro’ system, the Open Compute Project, and independent startups such as Oxide Computer.

The next logical step from here was to look at how they could optimise the processor silicon itself – and that’s just what they did. At first, this meant adding individual specialist processors, such as FPGA based chips, and Google’s Tensor Processing Units, each of which are aimed at very specific workloads and sat alongside a regular, general-purpose x86 processor.

The big development recently, though, is Amazon’s Graviton2 CPU, which would seem to be the first big attempt to offer a genuine ARM-based alternative to an all-purpose Intel or AMD x86 based system.

Amazon claims that Graviton2 can provide up to a 40% performance gain over equivalent x86 processors for a wide variety of common tasks, such as application workloads, microservices and the like.

We’re also perhaps starting to see the removal of another impediment to ARM’s growth in this space – the lack of ARM-based machines for software developers.

Apple’s move to ARM silicon

Earlier this year, Apple revealed plans to begin offering ARM-based versions of its Macbooks by the end of 2020. These will sit alongside current x86 based models and be built around an Apple-designed processor.

This could be a huge step. These machines are popular with software and web developers, so an awful lot of programmers (or, at least, non-Microsoft stack ones) could be writing and running code on machines that are ARM-powered themselves.

If you’re writing code on an ARM-based system, and there are ARM-based servers available to run your code in production at a lower cost for better performance – why would you rent the x86 servers?

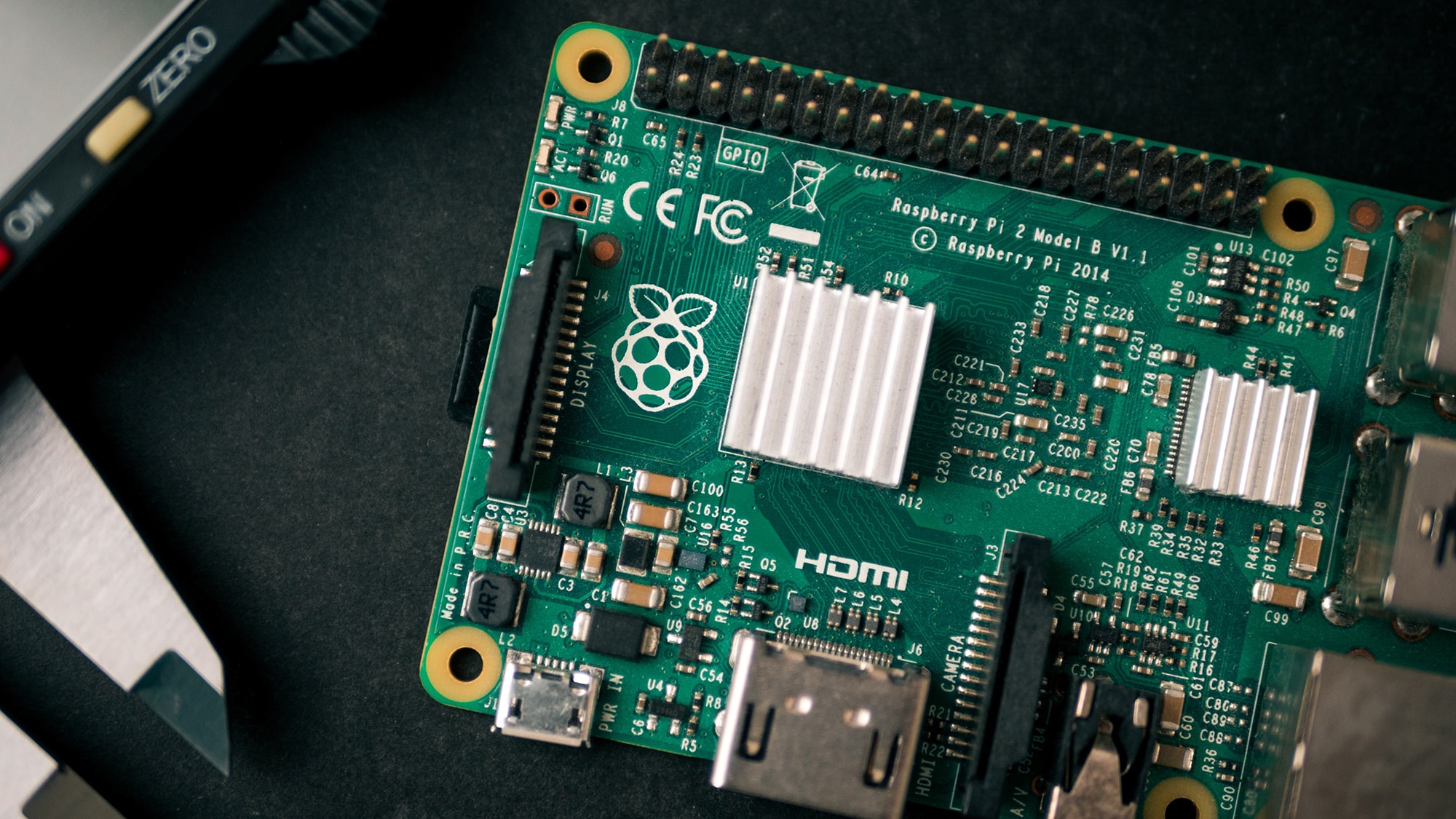

Raspberry Pi – less tunnel-visioned youth?

A third element of the convergence I see is in education.

Microsoft has long dominated the education space with its software that is written to work on x86 processors, which it offers to schools, universities and their pupils at special rates. This was (and still is) a canny move, as it grants the company an embedded advantage; graduates emerge from education familiar with the Microsoft ecosystem, and this, in turn, encourages businesses to adopt it.

As a side effect, this also entrenches the dominance of the x86 processor architecture in our lives. A state of affairs that Intel and AMD are no doubt very happy with.

In a small way, the Raspberry Pi project is challenging this. Built to expose young people to computer science at a young age, this simple, single-board computer is built around an ARM processor. It’s not their stated intention to introduce kids to ARM, but it is a nice side effect that those who take to programming on their Raspberry Pi will be using an ARM-based architecture.

The upshot is that common software used to run web applications now have pretty mature and fully supported ARM ports, think of most traditional web stack components such as MySQL, NGINX, and PHP.

Device convergence

Finally, I do see one more helping hand at play here; the move away from running applications locally in favour of applications that run in the cloud.

Though these programs will probably still be running on x86 based servers for a long time, it does start to reduce the number of day to day, local x86 applications that an end user’s device needs to be able to run.

All these cloud applications that run in web browsers are helping fuel a continuing convergence of computing platforms – meaning a lot more ARM-based tablets being used in the workplace.

Indeed, this is clearly a key motivation for Apple’s migration to ARM processors in their Macbook line. Unifying the architecture that their laptops, phones and tablets use will support deeper integration and make universal applications (and perhaps operating systems?) a possibility across multiple types of device.

Microsoft, too, dabbled with ARM processors back in 2012, creating WindowsRT for use on the ARM-based tablets. Admittedly this initiative was short-lived, but I can’t help wonder if they were just a bit early in their attempt.

If all goes well for Apple, could we see another more successful attempt by Microsoft to brings its products to ARM? There already community-produced ports of Visual Studio Code for ARM devices such as Chromebooks, and Windows on ARM is still a thing.

A market ripe for disruption

On the other side of the equation, we can see a server CPU market that is ripe for disruption. Intel, bereft of any serious competition, has been resting on its laurels and producing sub-par products for much of the last decade. A resurgent AMD has changed that recently, but the leaps in performance being made now would have been realised long ago in a more competitive market.

This is all before we consider the security issues and transparency concerns that have bedevilled x86 based CPUs recently, denting trust and energising those calling for change.

The bumps in the road for ARM

It might not be all smooth sailing to increase market share for ARM, though. There are a number of possible stumbling blocks.

First, there is a risk of competition from open-source competitors such as the nascent, open-source RISC-V, and a resurgent open-source PowerPC design. To its credit, ARM has already recognised this threat and has responded by making it easier and cheaper for firms to license their designs.

The catch here though is that since 2016, ARM has been owned by SoftBank (yes, that Softbank) who are now looking to extract as much profit as possible from a business they bought at great expense. This desire to turn a quick profit on ARM through a resale or floatation will only have hastened as SoftBank has watched other investments in companies such as WeWork run aground.

As a result, ARM has been under increasing pressure to jack up their licensing costs and boost revenue. This could hurt ARM’s market position in the long run, as if their pricing isn’t competitive, clients could consider redesigning their products to work with other instruction sets like RISC-V.

Ultimately though, if ARM hold their nerve, we might start to see a welcome change to the x86 stranglehold on the cloud – with all the benefits of lower cost, better performance, and less environmentally impactful tools that would bring us.